What does the smart mobility transition mean for modelling?

The opening plenary session at Modelling World asks whether rapid change means new models? In advance of my talk there I reflect on this question drawing on the work of the Commission on Travel Demand and the DEMAND Centre.

The first part of the question implies that we are in a world of rapid change. The rise of Uber, increasing autonomy of vehicles, electrification, on-line shopping… the list goes on. Change is happening for sure – but how rapid it is and how much of it is defined by changes to transport technologies seems much more open to question. I argue here that there are a number of trends, many of which our traditional approaches to understanding demand did not anticipate, that have been on-going slowly but for a period of time. Even when we see significant technological change coming to transport this will take some time to happen and when it does it will do so in ways which we currently would not anticipate. There is time to reflect on what sort of changes these new systems might engender but there is a need to start now given that we can be trying to support decisions that meet the needs of users 20 and more years into the future.

The second part of the question asks whether we need new models. Here I will argue that is the range, scale and nature of the uncertainties that should pre-occupy the discussion about the need for new models rather than a concern with rapidity of change. I will suggest that decision-making processes needs to accept that there does indeed exist a range of potentially different, yet still plausible, futures for how we get around in order for the focus of model development to address these challenges in a meaningful way. Models are decision-support tools and if we consider the questions which they are supporting to be different to those we have been examining then adaptation and/or innovation will be necessary. I will discuss why that is currently a challenge.

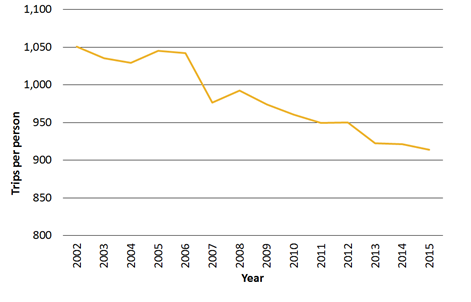

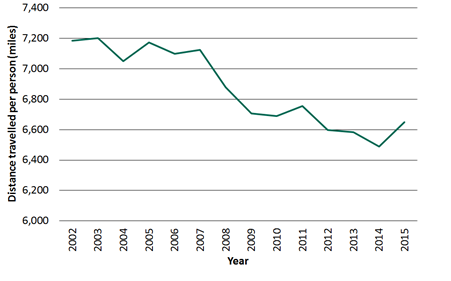

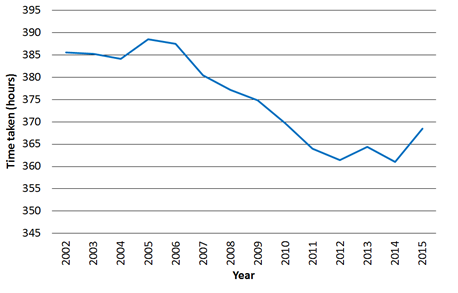

So, how rapid might change be and change in what? Looking back over the past decade, at an aggregate level as captured by the NTS for England, we have seen a decline in trip rates, trip distance and, more recently, the amount of time spent travelling.

Figure 1: Declining per capita annual travel trends (Data from NTS0101 2016 release)

There have been various important studies looking at the reasons behind these changes (see RAC Foundation, Independent Transport Commission and Department for Transport for start points). Some of the change is attributed to later uptake of driving licenses amongst younger people, some to rising insurance costs, increasing urbanisation, the changes to company car tax rules and a shift to virtual activities. However, none of these provides a complete explanation (see the work of Noreen McDonald), nor should we expect to find all of the answers within the transport sector. For example life expectancy is increasing by around 3 months each year and the average age at which women have their first child has risen by around one year each decade since 1975. If we look at wider social change which will impact on traffic patterns in the long-run then decisions such as raising the pension age, reducing pension levels, tightening immigration, healthcare innovations and continued growth in the pace and quality of communications infrastructure are all going to be very significant for mobility, but we cannot anticipate all of these changes by calibrating on historic data.

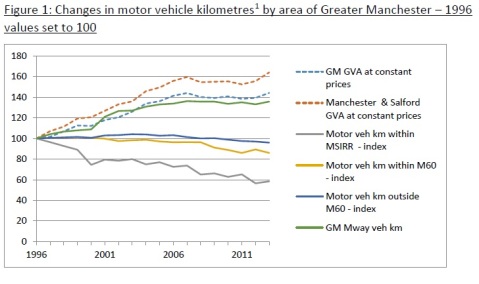

One interesting pattern to be emerging more strongly appears to be the decline in traffic in major urban areas excluding motorways (see Figure 2). People here seem to be able to assemble their patterns of mobility to meet their needs in less car intensive ways. Some of this results from growth in housing and employment in city centres which are associated with lifestyles which are less car dependent. Will these trends continue? Will they apply largely to those households without children? Does it mean car later rather than car never? Will car later mean car less (less intensive use of cars when they are owned)? It is in answering these sorts of questions that it becomes relevant to understand how Uber or Car Clubs are being incorporated into the everyday mobility patterns of people in different places. Many transport systems work much better with higher densities of demand and we might expect greater divergence in the degrees of multi-modality of people in different areas.

Figure 2: Changes in motor vehicle kilometres by area of Greater Manchester (1996 = 100). Source: TfGM submission to the Commission on Travel Demand

Given some of the gaps in understanding of how travel patterns have been changing, it seems important to try and understand how any new mobility options might be being accommodated in how people conduct their everyday life. If there is already evidence of travel being put together in different ways to those expected then we should avoid simply bolting on new elasticities and modal preference constants as a means of representing these changes. Questions such as whether people will send children to school in autonomous pods seem at least as important as to whether they can surf the web whilst on the motorway and therefore have a different time penalty on travel. It is important to remember that early adoption is not the same as mass adoption and we should be investing more now in understanding how they might influence what people do.

We should also be mindful of the longer term trends which were shown in Figure 1. Why will new technologies encourage people to start making more trips or to travel for longer? What will they stop doing if they are spending longer in vehicles? Whilst the substitution narrative is appealing it is unlikely to represent the full range of adaptations that occur (Did people use mobile phones just to make calls they used to do on their landlines?). There is also a tendency and a temptation to focus on the importance of the changes to transport modes and to forget that the other influences which have seemed so important to recent trends may continue or change in equally important ways. Will these changes accelerate or slow the adoption of some innovations as their mobility needs they might fulfil change? All of this poses some really interesting challenges to one of the key tenets of our approach to modelling and evaluation which is a reference case or business as usual. This would seem to be becoming more unusual.

So, to the second question, do we need new models? The answer to this, in the light of the potential for a quite different type of transportation system and ways of living, would seem to be a self-evident yes. How could modellers fail to try and incorporate and represent some of these changes? However, I would argue that we need to ask what we are using our models for before we jump in to improving them. All models are attempts to represent a complex world in as simple a way as is effective. Whereas the dominant influences of the decades up to 2000 could be seen to be those surrounding the growth of automobile use this is no longer the case. Given the range of uncertainties there seems to exist a range of future pathways which could diverge (and have already done so) from previously anticipated travel demand growth pathways. What does better modelling mean?

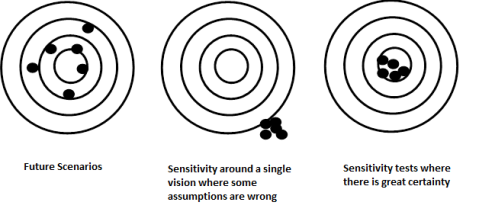

I am currently working with Glenn Lyons to draw the work of the CIHT Futures project together with that of the Commission on Travel Demand. One of the key areas we are grappling with is what models are being used to inform. As in Figure 3, we would suggest that what we need to aim for is a set of tools which provides insights about a range of plausible futures (left most image) – i.e. the dots are spread quite wide but around the centre of the target. This would imply that we take decisions that are robust in a range of futures (or that decision-makers understand that there would be circumstances where a particular course of action was not sound). If it is accepted that there is a lot of uncertainty then to continue to focus on one future and to develop our tools solely with the aim of testing lots off sensitivities around this creates an impression of accuracy which could be misleading (the centre image). The image to the far right would be some kind of Nirvana of great foresight. Outturn results of existing exercises suggest that we have never really lived there.

Figure 3: What are we aiming for?

So, I would suggest that there are parallel (but not unconnected) streams to be pursued in the future development of modelling. The first is a strand which develops a range of plausible demand futures. These will each develop different notions as to how society will change and how new technologies might become embedded within that. Where there is a need for more in-depth modelling then this will involve further development of modelling tools. This may be relatively minor such as understanding how smart technology impacts on interchange or more fundamental such as developing models around on-demand mobility access rather than car ownership. However, there will be a need to take an honest look at the requirements which the different futures suggest in order to determine whether current tools will continue to remain fit for purpose in representing these. Again here, there will be a growing need for transparency in terms of areas of limitation and uncertainty in how these different socio-technical futures are able to be represented by the tools at hand.

However, not all of the innovation or case for change can rest with the modelling community. Models are developed to find answers to policy questions. The current emphasis on being able to justify the number of jobs which a scheme will create or the degree to which agglomeration benefits or land value uplift will accrue itself implies a clear handle on these relationships and how they will evolve in the future. I think even here policy is running ahead of where experts in those fields believe the evidence is today. If the policy-making environment is not able to relax its obsession with a single BCR approach (down to the nearest decimal point) and consideration that the main way of supporting growth is delivered by the type of investments which supported the current travel paradigm then it is difficult to see why the mainstream modelling community would shift its developmental focus. It is necessary for there to be sufficient professional consensus, and then policy acceptance, that some kind of scenario based approach to policy making is a necessary part of the decision-making process before the door to more significant change can be opened.

So, to come back to the question posed by the plenary, does rapid change mean new models? It is not the rapidity but the breadth and scale of the changes to how society operates and the kind of mobility systems that might exist to support this that matters. Acceptance of a wider palette of futures and a need for a different approach to decision-making seems critical to the extent to which the demands on the modelling community are incremental or more fundamental. I am delighted to see this debate alive and kicking as I believe that if we do not get to grips with the real changes that are happening and what they mean for transparent decision-support then, at some point, our professional credibility will be challenged and potentially undermined.

Greg Marsden

This article is reproduced here with the permission of Landor as part of Modelling World 2017

Recognising uncertainty is not the same as accepting it

This week saw the first evidence session of the Commission on Travel Demand bringing together stakeholders from local and national government, academia and industry to discuss approaches to understanding demand in the sector. It ended with a debate on whether forecasting as had its day. The motion was defeated but that is not the same as saying we don’t need to re-examine the practice of thinking about travel demand in the future.

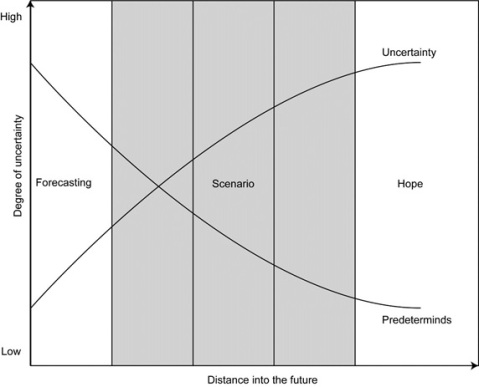

Robin Hickman shared the following image on uncertainty, time and techniques that match to the space you are operating in.

In the transport sector we largely deploy forecasting and, even where we use scenarios to think about different policy options, we return to making our decisions based on estimates of demand derived from a forecasting approach. Such an approach seems likely to risk biasing prioritisation of options towards those that are most compatible with the trends which underpin the forecasts. That is a problem if the futures really are potentially significantly different from where we are today.

It seems critical therefore to understand whether there already have been some important structural changes to travel trends which we have missed and whether there are likely to be more which fundamentally change how mobility is tied in to how society works. The evidence session shared several examples of trends which seem to be somehow significantly different to previous decades whether that is between central, inner and peri-urban areas or between different groups in society or for different journey purposes but what there is less evidence on is why that is happening. As an example, the chart below comes from evidence submitted to the Commission by Transport for Greater Manchester showing very different trends in traffic inside, outside and on the motorway network.

Some of the gap between projections and outturn was attributed to it being impossible to correctly foresee the ‘input conditions’ (wealth distributions, oil prices and congestion effects) and that structurally things aren’t perhaps so different. Even were that to be the main explanation, that line of thinking could marginalise whether the changes that result then create a different pathway for society as a result of the new conditions. Some of the change was attributed to completely new ways of doing things such as retail and work which is having a profound impact on what we travel for and how we might value travel in different activities.

It is important to make headway on these arguments. Despite there being widespread acceptance that in some way things are different this does not mean that there is acceptance amongst those taking decisions that this actually makes a difference to how we should take decisions. The assumption that demand in the future will be best supported by the assumptions of links between capacity growth and GDP growth remains intact and the attraction of a single central point forecast also remains strong. Greater clarity on the extent and reasons for an underlying change to how demand is evolving that challenges the current view would be necessary to convince that business as usual planning assumptions are built on sand.

Whilst I think there is a strong case to change the way we approach long-term planning I think we need to proceed with caution and build the arguments very carefully. In the debate I argued that forecasting is not dead. I did so for several reasons (other than that the purpose of a debate is to mount a coherent argument for whatever you are given to discuss!):

- There remain many decisions in the transport sector which are more short term in nature and/or which get revisited over time and therefore can be adapted. Longer-term uncertainty here is less important (see the earlier diagram)

- The approach to forecasting allows one to see how different explanators are changing over time and provide a baseline from which to understand stability and divergence from trends (incidentally no-one argues that forecasting is perfect and that it could not be improved)

- Even if we determine that other approaches would be better for longer-term decisions (and there does seem great potential here) there remain risks that those approaches would be hijacked to support the political will of the day as some critics suggest has happened with our current approach. There would need to be more work done to underpin the analytical rigour which supported decision-making in a world where more pluralistic futures were accepted (and there are examples being deployed in other sectors that may help).

- In short, we must not confuse the practice of decision-making that has built up around forecasting with the benefits that can be derived from the development and appropriate use of forecasts. They should be part of a toolkit of futuring rather than the only tool.

So, to conclude, there seems to be a growing body of evidence that suggests that there is a change in the role of mobility in society and therefore a level of uncertainty in future demand which goes beyond whether or not we have used the right GDP and oil price assumptions in a forecast. The future policy picture for mobility looks certain to add further uncertainty with the increasing automation of transport and changes to mobility service provision. Still greater change can be expected outside of the transport system which will also have profound impacts on what we travel for, where, when and how. That will be true whatever approach we adopt to decision-support and decision-making.

One of the uncertainties that we certainly face is whether decision-makers are ready to not just recognise this but to accept that it matters. A key challenge for research and practice is whether we can prove the need for change, persuade them of the evidence and provide tools which help them to understand and communicate this uncertainty to the various constituencies and systems to which they are accountable.

“Prediction is very difficult, especially if it’s about the future”

In this second post about the work of the Commission on Travel Demand I will explore the challenges posed by the quote from the scientist Nils Bohr that headlines this article.

Lets start by looking at the state of practice in the UK. All major infrastructure schemes are subject to an economic appraisal with an appraisal period of 60 years (which is 30 years longer than it used to be a decade ago). We produce long term estimates of demand using the National Trip End Model and a suite of other tools such as the National Transport Model and the Passenger Demand Forecasting Handbook. However, the demand futures upon which decisions are based are largely determined by what are deemed to be ‘reasonable assumptions’. The case for HS2 for example includes the following acknowledgment: “Despite the economic downturn there is little evidence to suggest the recent strong growth in long distance rail travel is about to stop. We therefore assume further growth in long distance rail travel but on a conservative basis that growth will stop in 2043” (HS2 Ltd 2011)

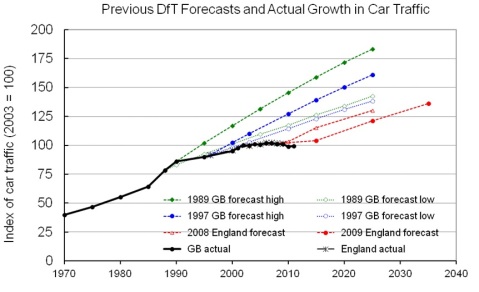

It’s a truism that the only thing we will know about any forecast is that will be wrong but that is not particularly helpful. So what is our history on forecasting? Phil Goodwin has long established the tendency of forecasts from the days of Roads for Prosperity to tend to overestimate road traffic with, at best, demand following the low growth ‘option’ as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: A history of forecasting difficulties for car traffic (Image courtesy of Phil Goodwin)

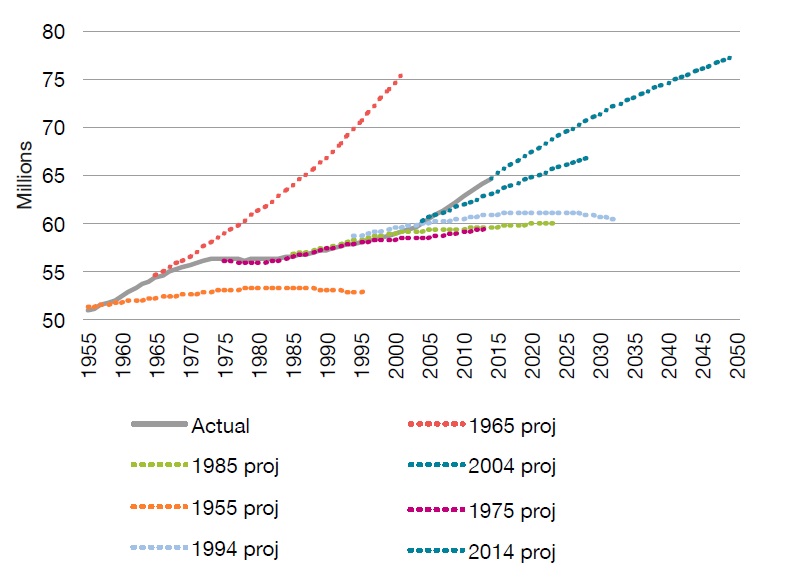

It is not that transport forecasters are bad at forecasting, it is just difficult to anticipate how the various variables in the models might move and which important variables that are not in the current approach will start to matter more. As an example, the National Infrastructure Commission is currently consulting on what the most likely population estimates will be. They review forecasting accuracy as shown in Figure 2. Look familiar? Clearly if the population forecasts are wrong then so will the travel forecasts be given the importance of population growth to total demand growth in our current approaches.

Figure 2: Previous ONS projections versus actual population 1955-2014 (Source: National Infrastructure Commission, 2016)

So, how do we deal with uncertainty about the factors that have underpinned our approaches to demand forecasting such as oil prices, population, income changes. The Department for Transport has been developing the National Transport Model to try and consider those trends which might be important. It led in 2015 to the production of five ‘scenarios’ of travel demand futures. They are not scenarios in the true sense of the term, more sensitivity tests on oil price, economic growth and the extent to which declining trips rates might persist. These are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Range of potential demand futures from National Road Traffic Forecasts (DfT, 2015)

This shows us that there is a range in 2040 traffic levels between the highest and lowest projection of 100 billion vehicle miles. Yes, 100 billion vehicle miles. That is 40% of the miles on our roads today. How do we deal with this kind of range of uncertainty? Currently we don’t, we adopt a preferred ‘scenario’ and continue with our demand analysis on the basis that this is the future under which all projects should be assessed.

None of the above allows for the changes to mobility that will come from social change such as the radical reshaping of the retail sector or changing travel expectations for the over 65s. Nor does it consider the transport system changes such as the introduction of TNCs such as Uber and Lyft, vehicle automation or electrification of the fleet which are being aggressively promoted.

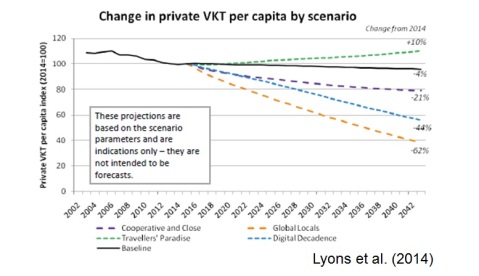

An alternative to simply adding more and more sensitivity lines that incorporate these factors is to try and develop scenarios which capture a plausible set of alternative futures under which decisions can be evaluated. Glenn Lyons and the New Zealand Department for Transportation underwent such an exercise producing a set of four scenarios (see Future Demand where Figure 4 is drawn from – well worth a read). The scenarios were then quantified and the headlines shown below.

Figure 4: Different demand scenarios for New Zealand: Source Lyons et al, 2014

Here again however the range of possible futures goes from a growth in traffic of +10% to –62%.

So, one of the questions we need to ask is whether the relatively near future of 2040 is so uncertain that we have to present decision makers with a range of outcomes which are this wide? Are there not some aspects of everyday life which root some parts of travel demand and are harder or slower to change? Which aspects, which areas, which communities are most and less open to change? Buchanan was surely faced with uncertainty on a level that parallels that which we face today as Traffic in Towns was assembled in the early 1960s. Many of the key insights were right or close approximations as to how demand might play out.

So, we must find a way forward which accepts that there are some demand uncertainties but which provides insight as to what and how much and equally importantly why? Some of these uncertainties are not somehow ‘out there’ waiting to happen but will be created by policy pathways we choose. Which aspects of future demand are most amenable to influence by transport policy and which will happen anyway? I hope the Commission will make progress through the call for evidence and our first three sessions on these questions so that we can move forward the debate on what this really means for decision-making.

Why we should worry about travel demand

Today marks the launch of a new Commission on Travel Demand which I am chairing. This is the first in a series of blog posts where I will explore the thinking behind the Commission and share insights from events, evidence and public meetings the Commission hosts during 2017.

I start by looking at why we should be interested in travel demand. There are certainly greater short run policy priorities out there such as job creation and promoting productivity and competitiveness in a post-Brexit world. In fact, talking about demand can be politically quite challenging as the idea of limiting growth in demand or managing demand in particular places or times of day can be contentious.

However, I would argue that we are in a period of significant change and uncertainty where there are numerous opportunities to shape the course of the future growth in travel demand. Many of these influences will also come from outside the transport sector. Some pathways will be more mobility intensive than others and that matters to the amount we will need to spend on infrastructure expansion and the extent to which we can meet our future environmental obligations.

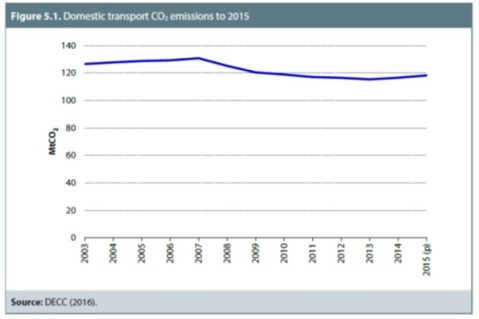

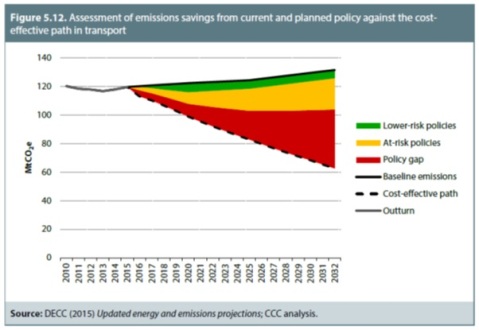

Starting with environmental obligations reminds us that we may need to pick less mobility intensive pathways in order to meet our carbon obligations. The UK Committee on Climate Change in its 2016 annual report to Parliament noted that whilst the UK as a whole has achieved CO2 emissions reductions of 38% on 1990 levels this has almost entirely been achieved through the power sector. If it is to remain on track for the fourth and fifth carbon budget periods to 2032 it requires major action in other sectors.

As the figures show, transport has shown comparatively little overall reduction and there is a very significant gap between what the Committee on Climate Change believes is a cost-effective reduction pathway and the set of transport policies we have in place today.

Whilst new technologies such as electrification of vehicles and increased biofuels offer reductions in emissions, the scale and pace of the transition from where we are today to an entirely technology-led solution seems unrealistic. In transport terms therefore this could mean travelling less far or less often, more by non-motorised transport and by more shared forms of mobility. To do this though, whilst maintaining social and economic progress, requires thinking well beyond just the transport system but to how participation in society is changing. This will help to understand where transport interventions could shape those futures in less rather than more carbon intensive ways.

In the next article in this blog series I will be reporting on insights from the US Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting in Washington which begins on Sunday 8th January. I’ll be talking at TRB on what different demand futures mean for infrastructure planning and maintenance and on what the changing employment market might mean for youth mobility. There will also be lots of debate about shared mobility and increasingly autonomous futures.

If you are interested in what you have read here and would like to contribute to the work of the Commission then please submit to the call for evidence which is open until mid February.

Professor Greg Marsden

Open Letter to Secretary of State for Transport

Below is the full text of an open letter, sent today, to the Secretary of State for Transport from 32 Transport Professors in the UK and two professional societies (Transport Planning Society and the Royal Town Planning Institute) asking for a fresh look at where transport strategy is heading and to look again at investment priorities.

The Rt Hon Patrick McLoughlin MP

Secretary of State for Transport

Department for Transport

Great Minster House

33 Horseferry Road

London

SW1P 4DR

Dear Secretary of State

Transport strategy – where should we be heading?

We write to you as a collective voice of professional concern and advice in relation to UK transport policy and investment plans.

Undoubtedly, the task of planning for the future mobility of the UK is more challenging than when we wrote to your predecessor in 2002. Operating within significant fiscal constraint the Department for Transport is seeking to stimulate economic recovery, tackle climate change and improve the well-being of the population. However, we are concerned that a perception of the economic imperative is leading to a series of important decisions on all of the major transport modes being taken in the absence of a coherent and integrated national policy framework for passengers and freight.

Recent evidence from the UK and internationally shows signs of road traffic growth leveling off, even after accounting for lower than anticipated economic growth. These trends are something which the Department for Transport has never forecast and which we are only beginning to understand. Whilst a growing population may well exert an upward pressure on demand, the basis for major infrastructure spending decisions appears to be changing.

There exists a range of views as to the importance of new transport infrastructure in stimulating economic growth. The evidence base is not as strong as you, or we, might wish it to be. Where real and substantial gains in connectivity and accessibility can be achieved (for example with city based investments such as CrossRail) the potential to unlock employment seems clear. As the 2006 Eddington Review pointed out however, the UK is already comparatively well connected, rendering the employment gains promised for many schemes difficult to realize.

Even were one to accept an economic imperative to invest in significantly expanding the strategic road network there is a well established evidence base that demonstrates that this will generate more traffic. Our cities are simply not equipped to take further growth in road traffic and the benefits of faster journey times on the strategic network risk being lost in greater congestion on local urban roads where the majority of journeys are undertaken. Across all of our networks we would urge a continuation or acceleration of smart demand management measures to ensure we get the best use of the infrastructures we already have – including our telecommunications infrastructures. The UK is a world leader in many aspects of this. Our service and knowledge-led economy should not be assumed to be as tightly coupled to road traffic for its success as it once might have been. There is substantial recent evidence, including the Local Sustainable Transport Fund and the Olympics, on the success of travel behaviour change programmes, underscoring demand management potential.

Integration across government is also important. On land use, changes to policy could well store up traffic problems for the future rather than encouraging economic growth. In reality, good transport and land use planning has prevented congestion and supported the economy, not held it back.

On funding, no progress has been made in the debate on how we should pay for improvements to the transport system. Understandably perhaps, your predecessors and the Treasury have ducked the issue of establishing a new congestion based system of pay as you go motoring. This could continue, but for how long? Tax revenues are forecast to fall as vehicle fuel efficiency improves to fulfill a major plank of your carbon reduction strategy. Increases in fuel duty to fill this hole have been a temporary fix, lack public support and fail to establish a stable platform for transport investment. There is a need to find a new way of charging for motoring as we move away from fossil-fuels.

We conclude, as we did in 2002 that policies on infrastructure, land-use, operations and prices must be consistent with each other if they are to offer a realistic chance of making things better instead of just accumulating long term problems. The past decade has shown how difficult integrated transport planning can be, but it remains the best hope to tackle the challenges you face. We urge you to work with us and the professional institutions in establishing a clear long-term national policy framework.

Full details of the letter and a press release will be posted on the Transport Planning Society website www.tps.org.uk

The Climate Change Act and Transport – 4 Years On

The Climate Change Act (2008) celebrates its fourth birthday today. The Act sets a world-leading target for reducing emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) by 80% by 2050 compared to 1990 levels. Four years on I reflect on what this has meant to the transport sector drawing on an on-going research project (http://www.its.leeds.ac.uk/transport-carbon/). Much more detailed analysis is available through the Committee on Climate Change website.

Transport is described as the sector that is most difficult to tackle, being so dependent on fossil fuel as its primary input. The evidence at least bears the lack of apparent progress out, with only a 1.7% reduction in emissions since 1990 despite quite significant improvements to vehicle fuel efficiency. These have, until recently been offset by traffic growth and by upsizing of the vehicle fleet. But has the Act galvanized new sorts of action and thinking in the transport sector?

To answer this we need to look at what the Act actually means. When it was first introduced, the then Labour government set about establishing departmental budgets as well as a series of interim overall carbon reduction targets. The Conservative-Liberal coalition has dropped sectoral targets and instead gone for a ‘Carbon Plan’ which provides indicative assessments of the impacts of a series of proposed policy tools. Of course, when set badly, targets have the potential to corrupt policy making, forcing actions to chase the end goal whatever the cost. That is not good policy. However, targets also provide a strategic focus which draw organizations together to meet common goals. Does it matter that the Department for Transport does not have a target for CO2 reduction?

This question has been explored through interviews with 59 governmental and non-governmental stakeholders in four city regions in England and Scotland joint with colleagues at the Universities of Sheffield, Glasgow and Lund. There seems to be little coherent or comprehensive action towards carbon reduction at a local level and, whilst the 80% by 2050 target is clearly known, there is a lack of clarity about what is expected locally. Even where local carbon targets are set they are deemed to be more a statement of hope than true intent.

Have local authorities failed then in their mission to support carbon reduction? This is complex. In part, they are muddling through on the back of limited evidence and significant uncertainty. For example, if there are major technological breakthroughs in decarbonising the car fleet then their role in reducing vehicle miles is diminished. No-one knows what will happen or how fast. Nonetheless, it seems that the imperative of economic growth has demoted discussion of travel demand reduction policies relative to that of promoting travel demand growth, albeit with some emphasis on public transport.

Our research found little difference in the ambition or effectiveness of carbon reduction policies across the different case study areas or countries. Although the Climate Change Act promises legally binding targets, it seems that it has done little to really stimulate a step change in thinking in the transport sector. Carbon certainly is not yet acting as a constraint in any meaningful way and it appears to have lost traction as an agenda since the downturn.

We will be meeting regional and national stakeholders in the coming months to develop policy recommendations and we would be happy to hear from any interested parties. Events will be held in:

- Leeds (29th November)

- Manchester (28th February)

- London (5th March)

- Glasgow or Edinburgh (9th April)

If you want to find out more or get involved please contact me g.r.marsden@its.leeds.ac.uk

Flood Survey Reflections

A team of researchers spent the weekend out interviewing people in Cawood, Naburn, Acaster Malbis and York talking to households and businesses affected by the flood. Fortunately the number of houses affected in the areas I visited were small compared with 2000 in part due to the slightly lower water levels and in part due to small improvements to the flood defences which, for example, kept one road out of Naburn open. Driving and walking around now, it is hard to believe that there was a flood, with the exception that Cawood bridge remains closed and riverside fields and caravan parks remain under water.

It is early days to be able to generalise about what the interviews found. However, the ones I did showed how varied the responses might be. For those who have jobs where work can be done flexibly from home there was little direct impact. That is, unless one also had children who were due to attend the school which was closed. This led to a series of traded favours amongst the community in the case that both parents worked. Arrangements were in some instances quite fragile. Interestingly no-one I spoke with described there as being anything other than an immediate loss, with work being flexible and understanding and workload simply being “caught up” over the coming week or two.

Food shopping patterns changed, particularly as home deliveries were unable to be delivered. Most people actually had enough in their fridges and cupboards to be able to get through with a little top up shop at a nearby garage or en-route home. Some of the longer-term residents had stocks of food in the freezer for just such an eventuality. It was surprising to a degree just how ‘normal’ this event was. For someone new to the area there was a sense of calm as the rising waters followed a pattern which others knew and understood.

We’ll find out more about business impacts over the coming weeks. I met with a farmer who had to make significant adaptations to their livestock housing and who lost a lot of arable crops at various stages of planting. It will take 2 to 3 years to get back in cycle there. A local caravan park was significantly affected but still had spaces on one high area. However, the lack of local bus service meant that those with motor homes that usually accessed York by bus left the site.

This will be my last blog post on the flood – we are moving now into a phase of data analysis and then feedback – both to the local authorities and parish councils and to the Disruption project www.disruptionproject.net

Floods stretch on – what are people doing to cope?

Friday afternoon. I’m lucky in that my kids are being looked after by friends in the village – all arranged during the various handovers that happened yesterday. I am in debt again so had better plan not to be working on the next school inset day!

Some reflections from people I’ve seen. Long diversions in place for cyclists and cars but its a nightmare getting into York with the A19 shuty and parts of the inner ring road. A neighbour suggested it would be faster to walk to York (we are 5 miles out). I reckon they are right. My daughter said last night and today. Can we keep it like this, its good fun, I’ve kind of got used to it. Perhaps its the fun of making it round the village in a dinghy or maybe not being at school. However, there is a sense in which this has all become quite normal – we are only using one car and need to share it. It takes a bit longer to get places and we’re probably doing a bit less than we were. Well that wouldn’t be so bad given how much we are overdoing it anyway.

I should add life would be a whole lot less complex if my wife wasn’t away for the weekend and I wasn’t trying to organise surveys to find out more about how everyone else is coping.

Been Affected by the Flood Like Me? – Take Part in Research

Many residents of York and North Yorkshire will have had and still be having travel plans upset by the current high water levels. I am leading a research project which tries to understand what happens to people when they are faced with Disruptive events of a whole range of different types (more details at www.disruptionproject.net). We would like to have short interviews with anyone who has been affected by the flood in any way – cancelled activities,missed work, school closure, long journeys and just more generally to understand how you coped.

To take part please contact Jeremy Shires

W: 0113 3435347

M: 07957 333 817

We hope to be surveying over the weekend and are happy to provide more details. In the meantime, hope you enjoy the photo below – and if anyone knows who is looking after my kids tomorrow that’d be good to know too!!!

Flood update

Got up at 6:50 today to come in to work for my meeting this morning. Had to wade very slowly up the road – not quite the 8:00am peak when it is high tide. Looks like most of the houses will be OK but the roads are impassable within the village.

Met the School Head on her way to check out the school at 7:30. First contacts are to the radio and local news channels then back home to post on the VLE – no way you can get kids to the school. Looks like it has a moat.

Cancelled the cleaner (very middle class) – will wait to see what unfolds at home with school shut. I am off tomorrow afternoon anyway as my wife is away so will probably fall to her today – may be some reciprocity amongst parents.